The Great Gantry, Queen's Island, Belfast

005 • Sir William Arrol

In late 1908, the dream of the next generation of ocean liners moved from the drafting table to the real world. But Harland & Wolff realized that they did not have the necessary infrastructure to construct these giant ships and so they cleared the existing slipways and looked for an engineer capable of building a ground-breaking new gantry under which both ships could be built at the same time.

There was only one man for the job, the world renowned Sir William Arrol who had built the Tay Bridge, the Forth Rail Bridge and Tower Bridge consecutively.

Sir William Arrol was arguably the most celebrated engineer of the Victorian age. His contributions, particularly in bridge building and the use of steel in construction, helped shape the modern world in ways that still resonate today.

Arrol's life is a testament to determination and ingenuity. Born into a family of weavers, he faced financial hardship early on. However, instead of being deterred, Arrol used his adversity as fuel for his ambition. From working in the mills at the age of nine to later studying blacksmithing, mechanics, and hydraulics in night school, his relentless pursuit of knowledge and self-improvement was evident from the very beginning. This strong work ethic would serve him well as he carved a name for himself in the engineering world.

By 1872, Arrol's entrepreneurial spirit had driven him to establish the Dalmarnock Iron Works, which would later become Sir William Arrol & Co. It was here that he would push the boundaries of what was possible, developing new techniques and tools that would revolutionize the industry. His hydraulic riveting machine, for example, was an innovation that increased both the speed and the quality of riveted connections, making structures safer and more durable. This technology would go on to be adopted widely across the industry, becoming a standard in construction.

However, it was Arrol’s bridge-building feats that earned him his most lasting fame. The Forth Bridge, completed in 1890, stands as a triumph of engineering. It was the first major bridge to be constructed primarily of steel, which was a bold move at the time, given the challenges and risks associated with the material. The Forth Bridge was not only the longest cantilever bridge in the world at the time but also a symbol of what was possible with steel construction. Its graceful yet imposing design remains an iconic part of the Scottish landscape to this day.

Arrol’s reputation as an engineer capable of overcoming the most difficult of challenges was cemented after the tragic collapse of the original Tay Bridge in 1879, which had led to a loss of public confidence in railway bridge construction. The collapse of the Tay Bridge had caused a national scandal, but Arrol was called upon to design and build the replacement. His successful completion of the new Tay Bridge restored faith in the safety and feasibility of rail bridges and solidified his status as a leading figure in engineering.

Not content with just his work in Scotland, Arrol's reach extended beyond Britain. In London, his company constructed the steel superstructure for Tower Bridge, one of the most iconic bridges in the world, known for its bascule design. Tower Bridge’s unique mechanism of lifting and lowering its bascules has made it a landmark and symbol of the engineering prowess of the late 19th century. It remains an enduring achievement of both Arrol’s skill and vision.

In addition to his work on bridges, Arrol’s company went on to build numerous other notable structures, both in Britain and abroad, ranging from railway bridges to industrial sites, and even major buildings in various countries. His legacy as an innovator and a pioneer in the use of steel for large-scale construction projects remains a fundamental part of the engineering world’s history.

Arrol's influence reached beyond just the realm of engineering; he was knighted in 1911 for his exceptional contributions to the field and to British industry. His work continues to inspire engineers and architects worldwide, reminding us of the power of creativity, perseverance, and innovation in overcoming the greatest challenges.

In many ways, Sir William Arrol's career exemplifies the spirit of the industrial revolution: bold, forward-thinking, and determined to make the impossible a reality. His bridges, and the innovations that came with them, will forever stand as testaments to his skill, vision, and relentless drive to push the boundaries of what was possible.

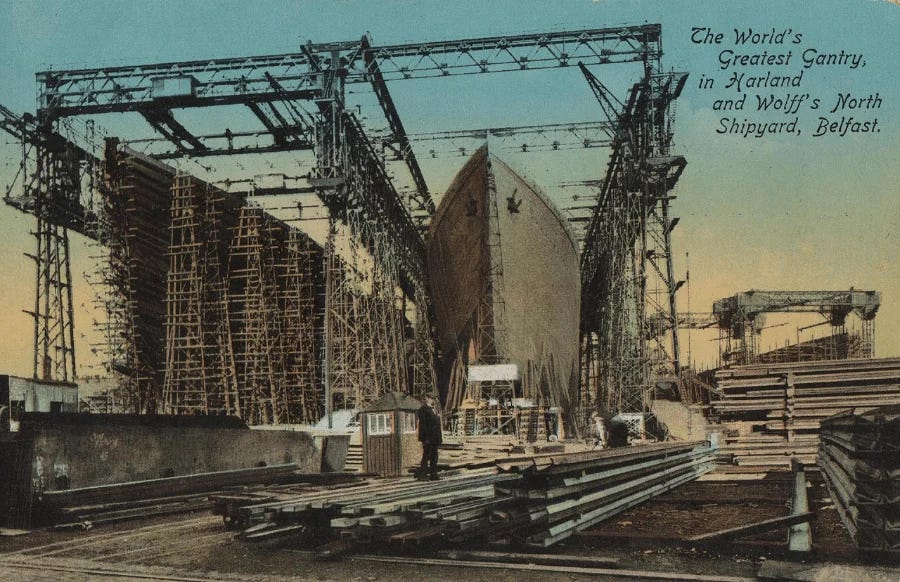

Before the Gantry, the northern end of the Queen's Island shipyard had four building slipways, each with gantry cranes above them. The cranes formed three crosswise gantries over each slip, with jib cranes working from each upright.

To accommodate the massive new Olympic Class ships, Harland and Wolff converted three of their already huge slipways into two bigger slipways. No 1 slipway remained and continued in use, with its original gantries. The two new slipways were numbered 2 & 3. (Belfast’s taxpayers bore the cost of razing three existing slipways to the ground to extend the berthing piers by 100 feet.)

The new steel gantry was erected over the two new slipways, custom built to accommodate both ships simultaneously and meet the needs of such monstrous vessels. Four thousand tons of concrete were poured for the foundations. The gantry itself was 840 feet (260 m) long 270 feet (82 m) wide, with a height of 228 feet (69 m) to the top of the upper crane, and was constructed with over 6,000 tons of steel. In the middle were the world’s largest revolving cranes; on top were four traveling cranes and at the bottom there was five walking cranes at either side. There were also four elevators to take the men to their places of work.

The gantry was built on three rows, 120 feet (37 m) apart, of eleven steel truss towers with three large truss girders between them, and lighter crosswise Warren1 trusses above this. The large girders provided runways for a pair of 10-ton overhead cranes above each way and lighter 5-ton jib cranes from the sides. The Titan crane, located along the centerline of the gantry, was a key piece of machinery in this operation. Its reach of 135 feet, combined with its ability to carry up to 5 tons closer in and 3 tons at full radius, made it ideal for fine-tuning the positioning of key parts of the ship. These cranes would often be used in tandem, with one crane lifting the bulk of a component while another adjusted its alignment, ensuring the ships were constructed with the utmost precision.

The gantry's design incorporated modern technology with ease of access for the workers who were constructing the ships. The electric lifts and long ramps ensured that workers could quickly and efficiently reach the necessary parts of the gantry without having to scale the vast heights manually. This helped maintain a continuous flow of work and reduced potential delays caused by transportation and accessibility challenges.

While Harland & Wolff's focus was on commercial vessels rather than military ships, the gantry was designed with a level of sophistication comparable to the naval shipyards of the time, albeit tailored to the needs of commercial shipbuilding. The facilities provided not only the necessary power and reach to handle such monumental constructions but also offered the precision needed to build the massive Olympic-class liners, which were set to redefine the standards of luxury and technology in passenger ships.

Overall, the gantry’s design and its associated crane systems played an integral role in the success of the Titanic and her sister ships. It allowed for the precise construction of massive ships in a relatively short time frame, setting a new standard for shipbuilding operations worldwide. The remarkable engineering behind the gantry demonstrated Harland & Wolff's ability to meet the immense challenges presented by the Olympic-class project and reinforced its position as a world leader in shipbuilding at the time.

By the end of that year, Harland and Wolff had built the tallest gantry ever that stood over the slipways known as the Arrol Gantry. And once the gantry was completed, Harland and Wolff started to hire shipworkers in record numbers.

The Arrol Gantry was not just a piece of engineering; it was an integral part of the landscape and history of Belfast. As the towering silhouettes of the Olympic and Titanic emerged within the vast steel framework of the gantry, it symbolized both the ambition and the industrial might of Harland & Wolff, and indeed of Belfast itself. The city became synonymous with these ships—magnificent vessels that represented the peak of human engineering and craftsmanship.

The sheer scale of the Olympic-class ships, with their towering frames and opulent designs, transformed Belfast's skyline. The river Lagan, too, had to be reshaped to accommodate them. The dredging of the river to a depth of 50 feet was no small feat, but it was essential to ensure that ships like Titanic could be launched with ease, given their immense size and weight. The new superliners' larger draft necessitated significant alterations to the harbor and river infrastructure—changes that reflected the global importance of Harland & Wolff and the White Star Line’s vision.

For decades, the Arrol Gantry dominated Belfast's industrial heart, a massive and unmistakable presence in the city. Its towering structure, echoing the scale of the ships it helped to build, became an iconic symbol of the city’s shipbuilding prowess. Louis MacNeice's evocative lines in Carrickfergus capture the essence of Belfast in that era: a city shaped by industry, where the clang of steel and the hum of shipbuilding were as much a part of life as the surrounding mountains and the coastal winds.

But as Harland & Wolff faced mounting financial troubles, the cost of maintaining such a monumental structure became untenable. By 1971, the gantry was demolished, marking the end of an era in Belfast's industrial history. The loss of the Arrol Gantry symbolized the decline of an industry that had once driven the city's economy and global reputation. Yet, the legacy of the Olympic-class ships—and the role the gantry played in their construction—lives on. Without that incredible feat of engineering, Olympic, Britannic, and Titanic would not have come into existence, and Belfast’s role in maritime history would not have been as indelible.

Even though the Arrol Gantry is gone, its legacy is cemented in the memories of those who witnessed it, as well as in the indomitable spirit of Belfast’s shipbuilding past. The Titanic story, tied so closely to that magnificent structure, remains one of the most poignant chapters in maritime history, and the gantry will always be remembered as the cradle of the most famous ship ever built.

005.1 Reconstruction of North Yard slips 2 & 3 and erection of Arrol gantry for building OLYMPIC & TITANIC (400&401), 1907-1908. Photographer Robert John Welch (1859-1936).

005.2 Sir William Arrol, Scottish civil engineer, bridge builder, and Liberal Unionist Party politician, (February 13, 1839 - February 20, 1913). Arrol died at his home in Seafield, Ayr on 20th February 1913 at the age of 74 years. He had been suffering for about 5 weeks from flu which had developed into pneumonia and from which he was making a slow recovery. During this time, he developed an abscess in his lower bowel which required surgery, but in his weakened condition the operation was too much for his body to cope with and he died the following day. When he died Arrol’s estate was worth £317,749, today the equivalent of over £20 million.

Although he had no children of his own, Arrol was very much a family man and left bequests in his will not only to his immediate family but also to his extended family. He also left many public bequests including: Glasgow Royal Infirmary, Glasgow Western Infirmary, Ayr Infirmary, Glasgow Eye Infirmary, The Higginbotham Sick Poor Nursing Association incorporated Glasgow Old Man’s Friendly Society and Old Woman’s Home, and The University of Glasgow.

005.3 ‘Section of Gantry over Slips Nos 2 and 3’, The Shipbuilder, 1911. A gantry being a crane system that manoeuvres over the top of a ship in a dockyard carrying materials and workers.

005.4 Arrol Gantry under construction, 1907-1908. Photographer Robert John Welch (1859-1936).

005.5 Colored postcard showing ‘The Great Gantries’, Harland & Wolff shipyards, Belfast 1911.

005.6 RMS Titanic under construction in the Arrol Gantry. The "Chester" anchored in the foreground.

005.7 The Great Gantry under construction, Queens Island, Belfast.

Footnotes:

In structural engineering, a Warren truss or equilateral truss is a type of truss employing a weight-saving design based upon equilateral triangles. It is named after the British engineer James Warren, who patented it in 1848.