The turn of the century was a period of profound upheaval for both the White Star Line and Harland & Wolff. It was a time when fortune and fate collided, altering the course of the companies forever. In 1895, Sir Edward Harland, the man whose vision and leadership had turned Harland & Wolff into a global shipbuilding giant, passed away. His death left James Pirrie to take full control of the shipyard, but it also signaled the end of an era. Harland's legacy was now in Pirrie’s hands, and while Pirrie had the drive and ambition to continue the company’s success, it marked the beginning of a new, uncertain chapter.

Then, in 1897, another blow was dealt to the shipping world with the death of Gustav Christian Schwabe, the financier who had helped Thomas Ismay breathe new life into the White Star Line. Schwabe’s passing left a void in the very foundation of White Star’s financial backing, further compounding the challenges the company would face in the years ahead.

However, it was the death of Thomas Ismay himself, on 23 November 1899, that truly marked a turning point. Only weeks after the Oceanic II had embarked on her maiden voyage—her grandeur a crowning achievement for the company—Ismay, the driving force behind the White Star Line’s rise, passed away unexpectedly. Unlike Harland & Wolff, where succession plans had been carefully considered, Ismay had made no serious arrangements for the future of the White Star Line. The absence of such plans left the company in a precarious position, adrift without a captain at its helm.

By default, the reins of the White Star Line passed to Ismay’s eldest son, Joseph Bruce Ismay, a man who now found himself thrust into the immense responsibility of steering the company forward. Joseph Bruce Ismay, though not yet the seasoned leader his father had been, would soon face the monumental task of navigating the challenges of the early 20th century, a time when the world of shipping was rapidly evolving, and White Star’s greatest challenge—its greatest triumph—was yet to come.1

On 23 November 1899 Thomas Ismay died and his son J Bruce Ismay took over as head of the White Star Line.

Ismay’s first order of business was to add more ships to the White Star Line fleet. Under his father Thomas, the company had only built one ship, the state-of-the-art RMS Oceanic. (White Star Line's first true vessel because she was actually ordered by Thomas Ismay). Ismay decided to build four ocean liners to surpass even this, officially called the ‘Big Four’. Their names were RMS Celtic, RMS Cedric, RMS Baltic, and RMS Adriatic—the company’s tradition that ships all ended in “ic.”

In 1891 Bruce Ismay was appointed to the board. Here he was responsible for deciding upon a strategy for White Star ships to surpass their rivals, in particular Cunard. Cunard had been putting their efforts into developing liners that could win the coveted Blue Riband for the fastest transatlantic crossing. White Star couldn’t compete with Cunard’s turbine engines so had to find a different strategy.

In 1902 he oversaw the company’s acquisition by John Pierpont Morgan’s2 International Mercantile Marine Company (IMM)3. As part of the deal Ismay continued as chairman of White Star, and in 1904 was made president of this huge shipping company giving him the resources to put his plans for the biggest, best, most luxurious ocean liners in the world in place.

When Cunard introduced Lusitania and Mauretania in 1907 the White Star Line immediately felt the challenge as people flocked to sail on the new Cunard leviathans. Lusitania and her sister were extremely fast, but both were notorious for noise and vibration. Ismay knew his line would have to build ships far superior to Cunard both in size and luxury if they were to compete.

In 1907, the chairman of Harland & Wolff, Lord William Pirrie4 and the chairman of White Star, Bruce Ismay, had dinner at Pirrie’s Belgravia mansion where plans were made about how to outmatch Cunard’s Lusitania and Mauretania.

Ismay's dream was for three ocean greyhounds, 900 feet in length, adorned with the finest of everything; silk, oak, crystal and gold. His giants would certainly be swift, but his intent was that their interiors rival even the most regal of palaces. The would be the most elegant ships ever to sail the oceans.

"The largest moving object ever created by the hand of man." — J. Bruce Ismay

As the White Star Line sought to redefine the future of transatlantic travel, Lord Pirrie, now in full control of Harland & Wolff, took Thomas Ismay’s vision for a new class of ships and brought it to life. He handed Ismay’s sketches over to his engineers, with his nephew, Thomas Andrews, managing the design department. Andrews, a visionary in his own right, worked tirelessly with his team to draft plans for the ships that would become legends.

Initially, the designs called for three funnels and four masts—an homage to the grand ships of the past. However, Pirrie and Andrews understood that the future was not in the masts of sailing vessels, but in the bold, sleek lines of modernity. These ships were to be the queens of a new era, not just ocean liners, but floating palaces that would embody the peak of human engineering. The decision was made to eliminate the multiple masts that marked the past and replace them with a single, powerful design feature: a fourth funnel. This funnel, however, would be a “dummy”—purely for aesthetic purposes and ventilation, adding to the grandeur and imposing stature of the ship. It was a bold move, but it was in line with the public’s perception of safety: ships with four funnels were seen as larger, more robust, and thus, safer.

The number of masts was reduced to just two—one forward, one aft—and these masts would carry the antenna for the Marconi wireless apparatus, another groundbreaking feature of the new vessels. But it wasn’t just their appearance that would set these ships apart. Safety was paramount in the design, and Andrews and his team made sure the Olympic and Titanic would be virtually unsinkable.

Fifteen vertical bulkheads were carefully placed throughout each vessel, stretching across the width of the hull and dividing it into watertight compartments. These compartments could be sealed off from the rest of the ship in the event of an emergency. Each of these watertight doors could be closed remotely from the bridge, ensuring that, even in the most dire of circumstances, the ship could remain afloat. In theory, the first four, or even five, of these compartments could be flooded without causing the ship to sink. It was a revolutionary design, one that promised the highest levels of safety the world had ever seen, reinforcing the idea that the Olympic and Titanic were not just ships—they were the epitome of human achievement, destined to conquer the oceans.

Unlike Cunard and other shipping companies, White Star Line had no intention of keeping the names of their monumental new ships a secret. As soon as construction began on December 16, 1908, the name Olympic was proudly displayed on the gantry of the new ship being built at Harland & Wolff’s slip number 2. Visitors and workers alike could see it, a bold proclamation of the future that was being forged before their eyes.

The scale of the Olympic class was unlike anything the world had ever seen. The original plans called for three separate slips to handle the construction of these colossal vessels, known simply as No. 1, No. 2, and No. 3. But as the design for the Olympic took shape, it became clear that these slips would need to be reworked to accommodate the immense size of the ships. The gantries were reconfigured, with No. 1 and No. 2 becoming the new hubs for the groundbreaking project.

The construction of the Olympic was a feat of engineering, but it was not just about size—it was about vision. White Star had set its sights on creating something that would redefine the oceans. The third ship in the Olympic class, originally planned to follow soon after the first two, would only be built if the first two vessels proved successful. For now, work on gantry No. 3 continued, but all eyes were on the ship being constructed in slip No. 2.

Every hammer strike, every weld on the Olympic was a step toward realizing a dream—one that would see the largest ship in the world glide into the waters of Belfast’s shipyard. The public watched, eager and fascinated, as the massive ship took shape. There was no question in anyone’s mind: if this was the future of ocean travel, the world would be watching.

On the fateful night of April 10, 1912, the RMS Titanic, the grand sister ship of the Olympic, left the shores of Southampton, bound for New York. She was a marvel of engineering, the largest and most luxurious ship ever built—unsinkable, the world believed. But as she sailed the icy waters of the North Atlantic, destiny had other plans. On April 14, the Titanic collided with an iceberg. In just 2 hours and 40 minutes, the ship, once the pinnacle of human achievement, sank into the icy depths of the ocean, claiming 1,496 lives in a tragic and unforgettable disaster.

Thomas Ismay, the man who had once built the White Star Line into a titan of transatlantic travel, found his name tarnished in the aftermath. Accusations flew in the press after it was revealed that he had entered a lifeboat while passengers remained aboard the sinking ship. The scandal broke him. Retreating from the public eye, Ismay settled in County Galway, far from the world that had once revered him. By 1913, he retired from his role as president of IMM and severed his ties with the White Star Line.

The Great War would change everything for the White Star fleet. During the First World War, several of the company’s ships were repurposed for military service. The Olympic, which had survived the Titanic’s disaster and proved her strength, was pressed into service as a troop transport. Her wartime service was highlighted by her daring and decisive actions on May 12, 1918, when she rammed and sank the German U-boat U-103, a moment of triumph in a sea of devastation. Meanwhile, the Britannic, the Titanic’s sister ship, had a more tragic fate. On November 21, 1916, she struck a mine (though many believed it was a torpedo) in the Kea Channel. The ship sank in just 55 minutes, but her lifeboats saved most of the 1,100 people aboard, with only 30 lives lost. After the war, the Olympic returned to passenger service, but the Britannic was left forever on the ocean floor, the largest liner to have met such a fate.

By 1927, the White Star Line was in financial turmoil. The line, once the ruler of the waves, had been purchased by Lord Kylsant from IMM. Under his leadership, however, the company’s fortunes spiraled, exacerbated by the Great Depression and Kylsant’s poor management. The last ship ever built for the White Star Line was the Georgic (II), launched on November 12, 1931. She began her maiden voyage on June 25, 1932, but by 1934, the once-proud line could no longer survive on its own.

On May 10, 1934, White Star and Cunard, long-time rivals, merged to form Cunard White Star. The British government injected nearly £10 million into the new company to complete Cunard’s Queen Mary, a behemoth that would dominate the seas for decades to come. But by 1936, all remaining White Star ships had been sold, except for the Britannic, Georgic, and Laurentic—with the Laurentic mostly laid up by 1935 and never returning to service.

By December 1949, the last White Star shares were purchased, and the once-glorious name of the White Star Line vanished from the world’s oceans, forever lost in history. Even Georgic, the last ship from the line, had been sold for scrap, leaving only the memories of the great ships that had once ruled the seas. The Britannic (III), her sister ship, completed her final voyage for Cunard in 1960, and soon after, she too was sent to the scrapyard. Her last journey from Liverpool, on December 16, 1960, marked the end of an era.

But not all was lost. The Nomadic, a tender built for the Titanic in 1911, managed to survive. After spending years in France, Nomadic was restored and returned to Belfast, where it was opened to the public as a living testament to the once-great White Star Line.

Though White Star is no more, the legacy of its ships continues. Cunard, now the proud owner of the Queen Mary 2, Queen Elizabeth 2, and Queen Victoria, stands as one of the largest and most prestigious passenger lines in the world. The echoes of White Star still linger in the waves, reminders of the age when Titanic ruled the seas and the world watched in awe as ships became legends.

The Queen Mary5 is now a hotel and tourist attraction in Long Beach, California.

Bruce Ismay’s dream of ocean leviathans was realized, but ultimately ended in tragedy. Friends and family members reported that Ismay almost never mentioned the Titanic in private. “It absolutely shattered his life,” his grandson said in 2012. A lonely figure in his later years, Ismay took solace in outdoor pursuits in County Galway, Ireland. He worked for the remainder of his life on a commission that oversaw a fund for the families of crew members who were lost with the Titanic. But the sinking of Titanic came to define his legacy, and today fascinates many as a much-mythologized moment.

004.1 Starboard near profile and profile of cased builder's model OLYMPIC/TITANIC with sign 'the largest ships in the world’. Photo, glass plate negative, Robert John Welch (1859-1936).

004.2 Photo of J. Bruce Ismay that appeared in the Daily Mirror on April 16, 1912.

004.3 Lord William Pirrie and Captain Edward Smith aboard Olympic, June 9, 1911.

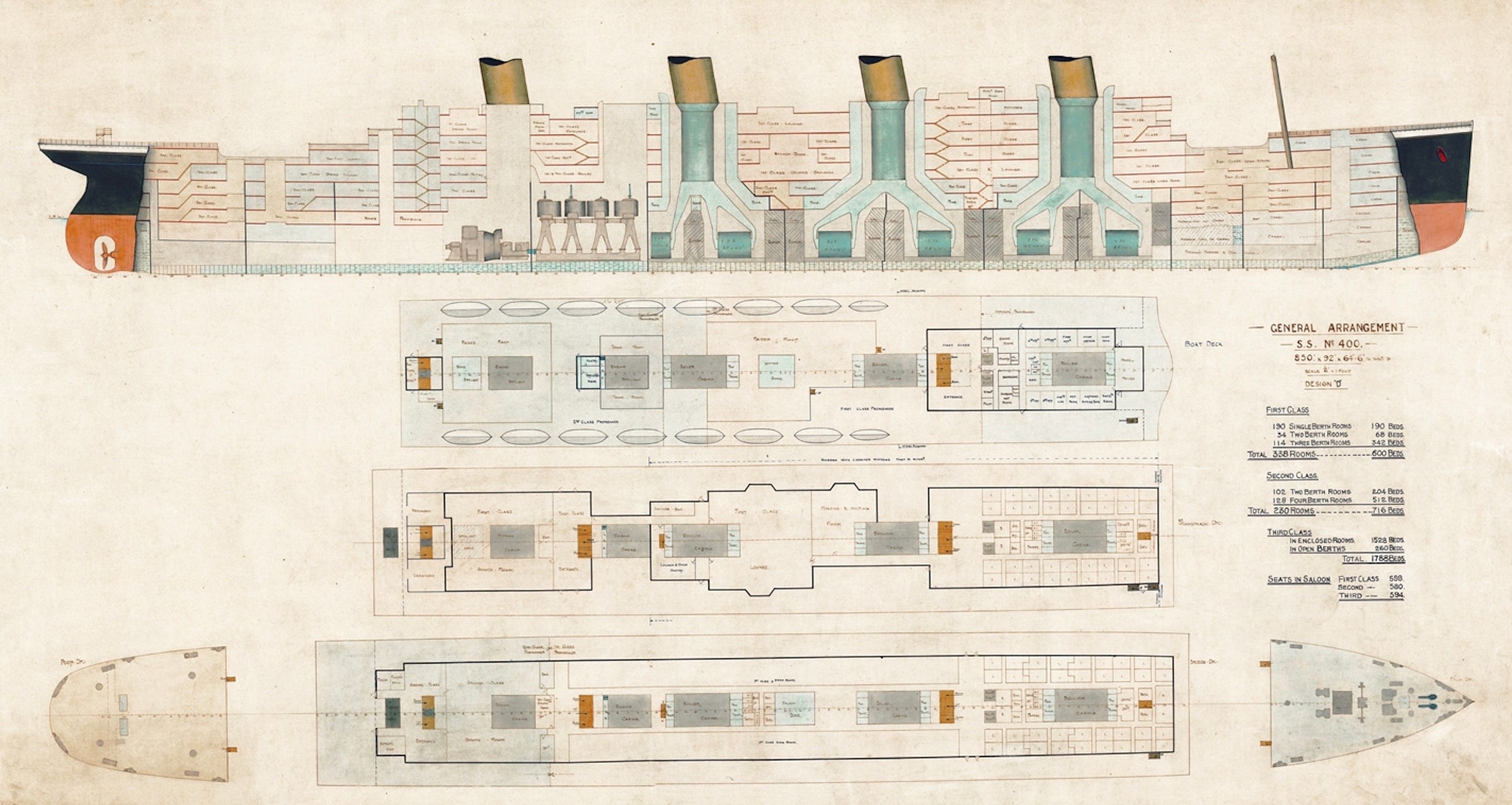

004.4 1908 ‘Design D’, General Arrangement Plan. Original Harland & Wolff design drawing of Ship No.400, Olympic and her sister ship Titanic, Ship No. 401. This design for Olympic and Titanic was approved in Belfast on July 29, 1908 by Bruce Ismay and other White Star directors. The drawing shows that Titanic incorporated a number of innovative naval design features, including the division of the hull into a series of virtually watertight compartments. The drawing also shows the huge amount of space occupied by boilers and engines. The 'dummy' fourth funnel is not connected to the coal-fired boilers, but is positioned above the turbine room. Its purpose was to enhance the prestige and beauty of the ship and it was also used for ventilation.

004.5 Queens Island Shipyard from the Albert Quay—a view to the gantries with a pier and boat docked in the foreground, circa early 1900s.

Footnotes:

Joseph Bruce Ismay, (born December 12, 1862, Crosby, near Liverpool, England—died October 17, 1937, London), British businessman who was chairman of the White Star Line and who survived the sinking of the company’s ship Titanic in 1912.

John Pierpont Morgan came from a family of successful financers. After beginning his career as an accountant, Morgan moved into business, reorganizing the railroads and amalgamating several steel companies to form United States Steel, the world’s first billion-dollar corporation. He also created General Electrical, by merging The Edison General Electrical and Thomas Houston Electrical. By 1891, the company was the dominant electrical equipment manufacturing firm in the US. Morgan also reputedly saved the US banking system during the panic of 1907, earning himself the title: “The Napoleon of Wall Street.

Morgan also amalgamated the majority of transatlantic shipping lines into the IMM- the International Mercantile Marine. Amongst those lines was the White Star Company, the company that owned the Titanic. This fact meant that technically speaking; JP Morgan was the owner of the legendary liner that could have cost him his life. Such was his interest that the ship was equipped with a private suite just for Morgan, complete with a promenade deck, and a personalized bath with specially designed cigar holders.

So it is no surprise to learn that Morgan had booked passage on Titanic’s maiden voyage. However, he never made it. The businessman had been enjoying a restorative holiday at the French resort of Aix, taking the sulfur baths for his health. At the last minute, he decided to extend his vacation and continue in Aix. The maiden voyage of the much-vaunted Titanic would have to go on without him. “Monetary losses amount to nothing in life,” he told a New York Times reporter who visited Aix several days after the sinking. “It is the loss of life that counts. It is that frightful death.”

While everyone knows that White Star Line was a British Company, fewer are aware it was owned by an American. International Mercantile Marine Company (IMM), was a wholly owned subsidiary of an American holding company owned by J.P. Morgan.

J. Bruce Ismay, chairman of the White Star Line, sold the company to J.P. Morgan in 1902, though as the RMS Titanic was a British ship, technically Morgan as an American could not own British ships. Nevertheless, Morgan took advantage of the loophole through his holding company and for all intents and purposes he owned the RMS Titanic.

IMM was Morgan’s grand scheme to monopolize shipping in the North Atlantic. It acquired control over the American Line, Red Star Line, Atlantic Transport Line, White Star Line, Leyland Line and Dominion Line. The company also arranged profit-sharing relationships with the German Hamburg-Amerika and the North German Lloyd Lines.

Ultimately, Morgan’s attempt to control the North Atlantic trade was a failure. IMM was over-levered and had inadequate cash flow to survive the volatility of international shipping. Two years after the sinking of the Titanic in 1914, IMM defaulted on bond interest payments and was put in receivership.

Following a series of mergers, IMM ultimately would be reorganized as United States Lines which would build the SS United States in 1952. She was the largest passenger ship ever built in the United States and still holds the record as the faster passenger ship on the North Atlantic run.

William James Pirrie, 1st Viscount Pirrie, KP, PC, PC, (31 May 1847 - 7 June 1924) [1] was a leading British shipbuilder and businessman. He was chairman of Harland and Wolff, shipbuilders, between 1895 and 1924, and also served as Lord Mayor of Belfast between 1896 and 1898.Although born in Canada, his grandfather and namesake, Captain

William Pirrie, was from Port William in Galloway, Scotland. After a spell in America he settled in Ulster, becoming a Belfast Harbour Commissioner in 1849. He sent his son James over to Canada to start a timber business but James died a few years later. His widow Eliza and two young children, Eliza and William (then aged 2), returned home and lived with Captain Pirrie in Conlig.

Young William was hugely influenced by his grandfather’s interest in ships and when he left school in 1862 aged 16 he joined Harland & Wolff as a premium apprentice. His rise in the firm was meteoric. Just 12 years after joining Harland & Wolff, he became a partner in 1874. Eventually he became chairman of the company and it was under his leadership that the firm opened a shipyard on the Clyde in 1902.

Pirrie served on Belfast Corporation and was Lord Mayor from 1896–7. He was also the first person to receive the Freedom of the City in 1898. Elevated to the peerage as a Baron in 1906, he became Viscount Pirrie of Belfast in 1921. He was appointed to the Senate of the new Northern Ireland Parliament in the same year.

He died while on business in Buenos Aires in 1924 and his body was brought home from New York onboard the Olympic. He was buried in Belfast City Cemetery.

The Queen Mary Hotel, 1126 Queens Highway Long Beach, CA 90802.