Titanic: From Paper to Steel

006 • Drawing Office No. 1

Harland & Wolff’s No. 1 Drawing Office, with its rich history, was not only the birthplace of some of the most famous ships in maritime history, including Titanic, but also a symbol of the shipyard’s craftsmanship, ambition, and dedication to excellence. Established in 1885, it became a central hub where the imagination of designers and the meticulous work of draftsmen brought to life the extraordinary ships that would define an era of ocean travel.

The Drawing Office was where the intricate details of ship design were transformed into reality. Each blueprint was drawn by hand, often with countless revisions and corrections, ensuring that every detail, from the hull design to the passenger accommodation, was perfected. This attention to detail was especially evident in the design of the Olympic class liners—Olympic, Titanic, and Britannic. These ships, with their grandeur and technological innovations, were products of years of labor and dedication within the walls of the Drawing Office.

The office itself had a striking feature—its arched windows, which allowed natural light to flood the space, fostering an environment conducive to creative and precise work. The light, however, was eventually blocked when the building was expanded in 1912, just before the launch of Titanic. Despite this, the Drawing Office remained a beacon of engineering ingenuity and a testament to the commitment of those who worked there.

The photograph from 1900, taken by Robert Welch, immortalizes this pivotal space. It features Roderick Chisholm, the chief draftsman responsible for the blueprints of Titanic, standing proudly in front of the Drawing Office. Chisholm, along with other members of the Guarantee Group, would later embark on Titanic’s maiden voyage in 1912 to monitor the ship’s performance. Tragically, like many of the Guarantee Group, Chisholm perished in the disaster, a grim testament to the risks that came with their dedication. His body was never recovered, and his fate remains tied to that fateful night in the icy waters of the Atlantic.

The Guarantee Group itself was a crucial part of the Titanic’s crew. Originally, nine members were planned for the group, but only eight made it aboard the ship. Their presence was seen as a mark of quality and assurance for the White Star Line and Harland & Wolff. However, their tragic end during the sinking of Titanic underscored the unpredictability of even the most meticulously designed vessels.

Samuel James Donnelly, another important figure from the Drawing Office, also made his mark in the history of the shipyard. Starting his career at just 15, Donnelly worked his way up through the ranks, becoming a respected chief ship draughtsman. His contributions were not only seen in the Titanic design but continued through his later work, including the design of the Canberra, the last cruise ship built in Belfast. His legacy in ship design was carried on through his son, Gilbert, ensuring that the family’s connection to the craft lived on for generations.

The Drawing Office, often referred to as the ‘Main Offices’, was built to reflect the prestige of Harland & Wolff. Unlike many shipyard offices, which were temporary and utilitarian, the Drawing Office was designed with permanence and quality in mind. The shipyard’s expansion across Queen’s Island mirrored its growing importance, and the permanent, light-filled Drawing Office served as a physical manifestation of the company’s rising stature in the world of shipbuilding.

Today, the No. 1 Drawing Office stands as a symbol of the artistry, skill, and vision that went into the construction of Titanic and her sister ships. The dedication of the men who worked there is immortalized in the legacy of these great ships, and the Drawing Office itself remains an important historical landmark in the story of Belfast's shipbuilding history.

Preliminary designs began in the Harland and Wolff Drawing Office in June, 1907. On July 29, 1908, the design for the Titanic was approved.

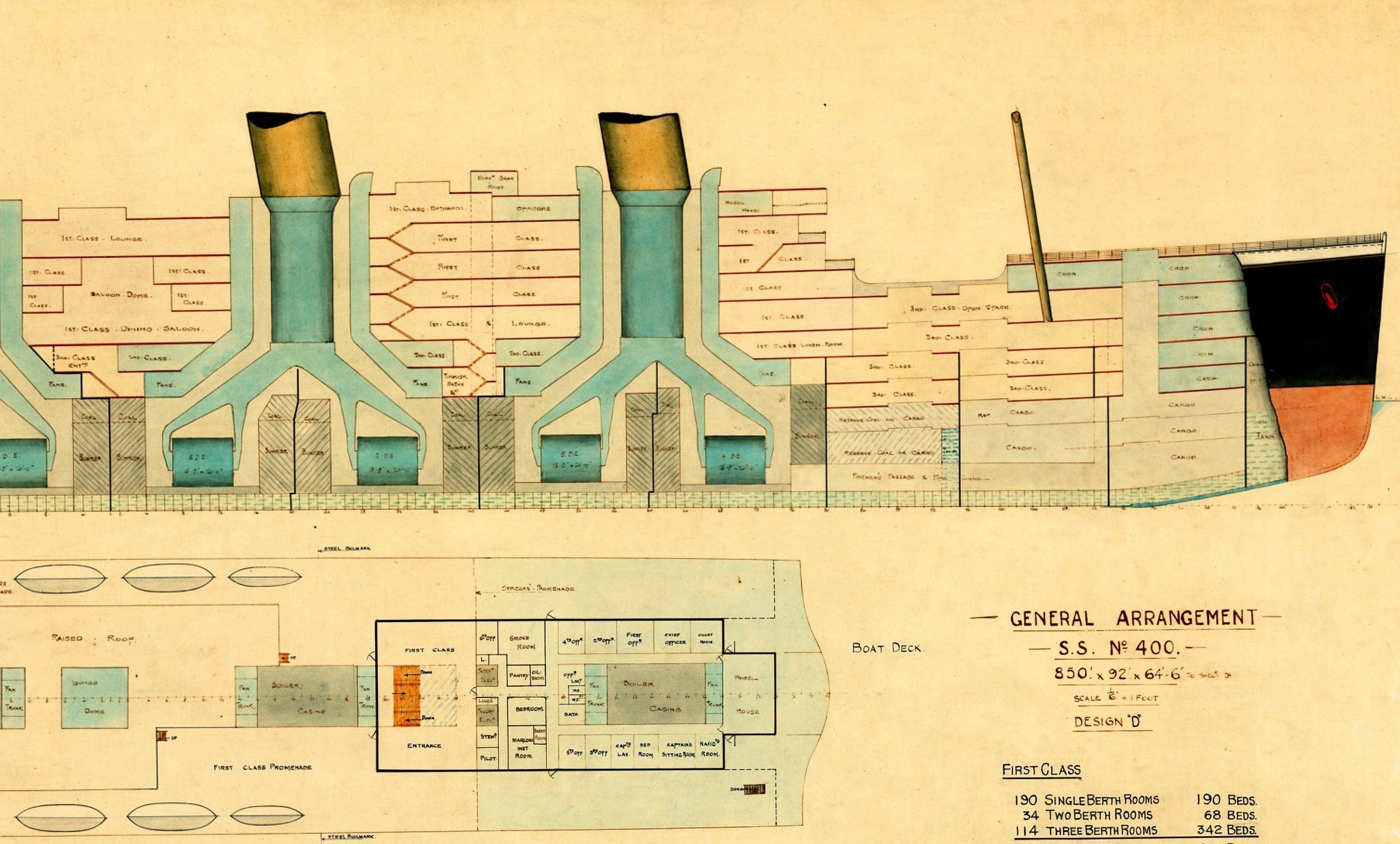

The early design concepts for the Olympic and Titanic provide a fascinating look into how these iconic ships were conceived before their final designs were realized. Known as "Design D," this version offers a glimpse into how the ships might have looked if certain design elements had been implemented, revealing some key differences from the final versions that would go on to become legends of maritime history.

One of the most striking aspects of Design D was the layout of the lifeboats. Unlike the final ships, where lifeboats were distributed across the boat deck with special attention to maintaining symmetry and functionality, Design D proposed an arrangement that placed all 16 lifeboats at the aft end of the boat deck. This included the 14 standard lifeboats along with the two smaller cutters. The lifeboats were evenly spaced on both sides of the ship, situated behind the second funnel, with the two cutters positioned further forward, closer to the bow. This layout mirrors the lifeboat arrangement of Adriatic, the last ship of the Big Four class, which was similar in design to the Olympic-class liners.

This early arrangement would have had a significant impact on the overall profile of the ships, altering the visual aesthetic and possibly the balance and functionality of the deck. The decision to have all lifeboats positioned aft might have made sense initially but would later be reconsidered in favor of the more balanced distribution seen on the final designs, which was a more practical approach for the safety of passengers in the event of an emergency.

Another notable difference in Design D was the omission of a mainmast, leaving only a foremast. This change had broader implications for the ship's overall structure and functionality. The final design of both the Olympic and Titanic included two masts, with a wireless aerial strung between them. The aerial system was a crucial part of the ships' communications capabilities, especially for the Titanic during her fateful maiden voyage. Had the single-mast configuration been implemented, the positioning of the wireless equipment would have been entirely different, and it’s likely that the wireless system would have been less effective. This could have had a significant impact, particularly in the case of Titanic, where the ship's wireless equipment played an essential role in receiving distress signals and communicating with nearby ships, although it was ultimately overwhelmed during the disaster.

Wireless communication, although in its infancy at the time, was beginning to be integrated into ships as a safety measure. The evolving technology likely wasn’t a major focus during the initial stages of design, but as it became more refined and critical, changes were made to accommodate the new systems. The single-mast design in Design D would have left the Olympic and Titanic at a disadvantage, especially when considering the advancements in wireless technology that would play a vital role in later years.

These early design concepts also reflect the challenges Harland & Wolff faced as they sought to balance aesthetic considerations, practical functionality, and emerging technological needs. The inclusion of lifeboats in a more centralized location on the boat deck and the adaptation of the mast structure highlight the shipyard's evolving approach to shipbuilding. Although many of these early ideas were abandoned in favor of more functional and technically refined solutions, the designs provided a foundation for what would eventually become two of the largest and most luxurious ships of their time.

In summary, Design D serves as an important stepping stone in the development of the Olympic and Titanic, showing how early concepts were refined and altered as new challenges and technological advancements emerged. The shift from a single mast to two, and the revised lifeboat arrangement, demonstrate how the final ships were fine-tuned to meet the demands of both safety and luxury, ultimately defining the legacy of the Olympic class.

The construction of the RMS Titanic at Harland & Wolff shipyards in Belfast was a monumental feat, not just of engineering but of labor and human effort. At the turn of the 20th century, the shipyard was one of the largest and most advanced in the world, employing nearly 15,000 workers—with more than 12,000 people directly contributing to the making of Titanic. This vast workforce was essential to the ship's creation and played an integral role in turning the idea of the Titanic into a tangible reality.

The ship's construction was not a solitary endeavor. It was made possible by decades of investment in Belfast’s port facilities, undertaken by the Belfast Harbour Commissioners, who expanded the harbor to accommodate the growing shipbuilding industry. These investments laid the foundation for the construction of ships like Titanic, making it feasible for Harland & Wolff to undertake such a massive and ambitious project. Without these advancements, it's likely that Titanic wouldn't have been built in Belfast at all.

The workforce was made up of people from diverse backgrounds, with skilled workers drawn from across Europe. Italian stonemasons, Portuguese draftsmen, and British tradesmen converged on Queen’s Island to contribute their expertise. It was not only local labor that was involved—people from all walks of life, including cabinetmakers, tile setters, steamfitters, riveters, and riggers, worked on the ship. Even subcontractors from outside Belfast supplied everything from English cutlery to Belfast linen. The production of Titanic became a citywide effort, involving virtually every aspect of life in Belfast, from grocers to doctors to hackney drivers.

The city itself was buzzing with activity. At the time, Belfast was home to around 390,000 people and was the fastest-growing industrial city in the world. The shipyard’s operations had a wide-reaching economic impact on the city. Whether it was the local pub, where teams of riveters gathered every Saturday to receive their pay, or the provisioners who stocked up on supplies needed for the ship, nearly every part of the local economy was linked to Harland & Wolff’s success.

Despite the booming industry, working conditions were hard and dangerous. The typical workday was long, starting at 6 a.m. and ending at 5:30 p.m. Workers had little room for error—being late or losing a tool meant a loss in pay. Even attending the launch of the ship, an event they had worked tirelessly toward, was penalized by the loss of a day’s wages. Meals were taken outside under the massive hulls of the ships, while management, nicknamed “the Hats” for their distinctive headwear, enjoyed more comfortable surroundings indoors.

Although workers received only one week of vacation per year and had minimal time off during Christmas and Easter, the wages earned—about two pounds per week—were considered decent for the time. It was enough to support a family, but not much more, especially given the physically demanding nature of the work.

Building Titanic was fraught with danger. Riveters, who were among the most respected but also the most at-risk workers, spent their days working in dangerous conditions. The riveting process was done by hand, with red-hot rivets hammered into place to seal the steel plates of the ship's hull. This was often done at great heights or in cramped spaces. Titanic required over three million rivets, each one representing the dedication and skill of the workers who performed this dangerous task. Sadly, at least two men died during the construction, and some estimates suggest as many as eight workers lost their lives during the building of the ship.

The story of the Titanic is often told through the lens of luxury and tragedy, but its true origins lie in the grit and labor of the thousands of men and women who made it possible. The ship wasn’t just built with steel and wood; it was forged in the fire, sweat, and determination of the people who toiled in Harland & Wolff’s shipyard. Titanic's legacy is not just that of a magnificent ocean liner, but also the legacy of the workers of Belfast, whose labor built not only a ship, but also a city that would forever be tied to its creation.

As the global shipbuilding industry faced a significant downturn in the latter half of the 20th century, Harland & Wolff found itself grappling with the shifting economic landscape. The decline of traditional shipbuilding meant that the iconic shipyard had to evolve and adapt to survive. A significant part of this transformation involved the company’s shift towards the construction of oil rigs and offshore platforms in the 1980s. These new industries, while keeping the shipyard active, marked a departure from the glorious days of ocean liners like the Titanic. Despite these efforts to diversify, the pulse of the once-vibrant shipyard began to slow, signaling the end of an era.

The Drawing Offices were constructed with the same battleship quality steel as Harland and Wolff’s ships.

The Headquarters Building and Drawing Offices, which had long been the heart of Harland & Wolff’s innovative design work, became a quiet reminder of the shipyard’s past. From 1900 until 1989, these spaces had been where countless designs, including the plans for Titanic, were conceived and meticulously drawn. However, by 1989, the building was officially vacated, and for nearly three decades, the rooms that once echoed with the sounds of draftsmen and engineers were left to sit idle.

The Drawing Offices—the very place where the legend of Titanic was brought to life on paper—stood silent, slowly becoming a fading monument to a golden age of shipbuilding in Belfast. As the shipbuilding industry in the city dwindled, the Headquarters Building and its once bustling spaces were left behind, vulnerable and neglected. The situation became so dire that, for much of the 1990s, the building was considered ‘at risk’.

However, the importance of the Headquarters Building was never overlooked, and in 2002, the building was listed, formally acknowledging its architectural and historical significance. Yet even with this recognition, the building remained largely unoccupied and under threat for many years.

In 2007, there was a significant turning point when the southern wing of the building, the former Administration Block, was renovated and repurposed as Titanic House, housing the offices of Titanic Quarter Limited. This restoration marked the beginning of a shift toward preserving the legacy of Harland & Wolff and the iconic ships that were built there.

Then, in 2016, a landmark moment in the building’s restoration came when a £5 million grant was awarded by the Heritage Lottery Fund to help fund a new restoration project. This partnership, involving the Titanic Foundation, Harcourt Developments, and the Heritage Lottery Fund, aimed to transform the historic building into a unique boutique hotel. The restoration would not only provide the public with access to a long-neglected heritage building, but it would also allow for the preservation of a vital part of Belfast's industrial heritage—the very site where some of the world’s most famous ships were designed.

In its new form, the Headquarters Building has found a new life while still honoring the legacy of Titanic and Harland & Wolff. The building’s restoration is a testament to the enduring importance of Belfast’s maritime history and its ability to adapt and preserve its past while embracing the future. The restoration also serves as a tribute to the men and women who built the iconic ships that put Belfast on the map as a global shipbuilding hub. The Titanic Quarter has now become a place where history and modernity coalesce, and the Headquarters Building, once left to decay, has been given a new purpose and a future as part of the city’s vibrant redevelopment.

Today, Drawing Office Two has been transformed into a stunning centerpiece of the Titanic Hotel Belfast, standing as a powerful tribute to Belfast’s maritime heritage. Once a quiet, dormant space where some of the world’s most iconic ships, including the RMS Titanic, were meticulously designed, this historic room now hums with the energy of visitors, echoing with the history of the shipbuilding legacy that once defined the city.

Beneath the soaring three-storey barrel-vaulted ceiling, the atmosphere remains one of reverence for the craftsmanship and ingenuity that went into the design of the Olympic-class liners. The bar—set within the heart of this grand space—pays homage to the past through its remarkable design. The 342 octagonal and 378 diamond-shaped Villeroy & Boch tiles that adorn the bar’s surface are a direct connection to Titanic’s past. These tiles were uncovered during the restoration of the Harland & Wolff building and were from the same batch used to decorate the interiors of Titanic and her sister ships, Olympic and Britannic. These restored details offer visitors a direct link to the grand liner’s luxurious interior.

The intricate plasterwork on the ceiling, painstakingly restored, reflects the craftsmanship of the artisans who originally worked on the interiors of Titanic and her sister ships. Their skills and attention to detail, which once brought the ship’s interiors to life, now serve as a reminder of the immense talent that was poured into every facet of Titanic's design.

Among the many historical spaces preserved within the Titanic Hotel, perhaps none is more poignant than the former office of Thomas Andrews, Titanic's chief designer. It was here in this room that the telegram arrived, bearing the devastating news that Titanic was in distress, an event that would forever shape the course of history. The space remains one of the most emotionally charged areas of the hotel, a physical manifestation of the tragic fate that befell Titanic, and it continues to serve as a place of reflection for those who visit.

The restoration of the Drawing Office Two and its transformation into the Titanic Hotel has brought new life to this iconic space, making it accessible to the public and preserving its rich history for future generations. As visitors walk through the restored halls and rooms, they are not only stepping into a piece of Belfast's industrial and maritime past but are also immersing themselves in the incredible story of Titanic—a story that still resonates deeply within the heart of the city and the world.

CORRECTION: There is actually a "Design A" at the Ulster Transport Museum. The "Design D" as it is posted above is the promotional drawing that was shown to the press in order to promote the new to be build ships at H&W. There are parts with tracing paper where the alterations for Titanic where made on. There's also a 33ft long profile plan on display at the Titanic Experience in Belfast which was made for the British Inquiry.